Scientific conservation

The title ‘Musée de France’ was set up by law of the 4th January 2002. This law defines a museum as ‘any permanent collection of items, the protection and display of which are of public interest and organised in such a way to provide the public with knowledge, education and an enjoyable experience’.

The ‘Musées de France’ are obliged to:

a) Protect, restore, study and add to their collections (heritage character of a museum)

b) Make their collections accessible to the broadest possible audiences

c) Create and implement educational and display tools, that will ensure everyone can access culture

d) Contribute to the progress made in knowledge and research, and in making it available to the public.

The four key criteria in obtaining the title are:

a) to be managed by scientific staff members with experience from the regional or national cultural sector (curator or assistant curator);

b) to keep an updated inventory of collections;

c) to draw up a scientific and cultural plan (PSC) detailing the key objectives;

d) to have access to an education department, either within the museum or in partnership with other museums.

The collections are the very heart of the museum: they are legally protected as national treasures. The collections belonging to the State and the regional authorities are:

a) INALIENABLE (they cannot be sold);

b) IMPRESCRIPTABLE (the owner can reclaim his property at any time);

c) NON-SEIZABLE (they cannot be seized by a creditor).

The museum is responsible for protecting and showcasing the collections today, to ensure they are passed on to future generations.

CONSERVE

The collections are the heart of the museum. The top priority for the Conservation team at the museum is to do everything necessary to ensure the conservation of the collections: security staff for monitoring (preventive conservation), direct work carried out on damaged artworks (curative conservation), and a close eye is kept on the inventory as well as ten-year stocktaking. All of these duties are carried out on a daily basis by the Conservation staff, and were also important when the collections were first installed in the Musée de la Romanité when it was built.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM-CC) defined “conservation-restoration” as all the measures necessary to safeguard tangible cultural heritage so it is preserved for present and future generations. Conservation-restoration includes preventive conservation, curative conservation and restoration (see next section). The goal of preventive conservation is to avoid any sign of wear in the materials and so in heritage objects. To do so, the environment in which the objects are displayed must be controlled: the temperature, relative humidity, the light, materials used to protect/package them, handling. Indirect measures and actions are implemented, that do not change the appearance of the objects. Preventive conservation is barely visible but essential in ensuring collections are managed correctly. However, curative conservation comes into play when an object begins to show signs of wear. This time, the actions needed are direct: the object is treated to stop a process which could eventually damage or even destroy it (desalination of ceramics, stabilisation of metals, removing moss or insects, etc.). These actions generally modify the appearance of the object.

During the significant work carried out on the collections prior to the creation of the Musée de la Romanité, other jobs that are less well-known by the public but still essential in ensuring the conservation of the collections were carried out:

a) checking the inventory, a specific administrative document that officially attests to the ownership of an artwork, either by the museum itself, or to a public collection;

b) ten-year stocktaking, which was made compulsory by the law of 2002, and involves checking each piece is present and noting its conservation condition, on-site;

c) collections are digitalised and entered into a database to make management much easier and more efficient;

d) each object was dusted, measured, examined, and photographed by members of staff specifically entrusted with this mission.

The sanitary conditions of the whole collection were also checked, in partnership with curators and restorers specialised in different fields: ceramics, glass, metal, stone and organic materials. And finally, the small and medium-sized artworks were packed and transferred to another building, in accordance with the recommendations issued by the curators and restorers. This operation was carried out in-house.

RESTORE

The creation of a new visitor’s tour at the Musée de la Romanité, based on the scientific and cultural plan (PSC) drawn up by the curator, was also an opportunity for some rather significant restoration work on the chosen artworks. According to the definition put forward by the International Council of Museums (ICOM-CC), the term restoration refers to any direct actions on the artwork, mainly for aesthetic and museographical reasons. You do not need to have noticed any dangerous damage or wear, as with curative conservation (see the previous section).

How an artwork is restored is decided upon by the curator, assisted by a multi-disciplinary team of restorers and curators, art historians and scientists. Each restoration is preceded by thorough research. Three key rules must be respected each time: the reversibility of the materials used, visibility of the work for everyone and compatibility of the restoration materials with the artwork’s original materials. The main purpose of restoration is to allow visitors to understand the object better: the reasoning behind this type of work is therefore often related to the museum tour itself, even if sanitary reasoning can also come into play. In most cases, restoration changes the appearance of the piece. The Musées de France are obliged to submit each restoration project to a regional scientific committee, for prior approval.

The work carried out on the collections of the Musée de la Romanité before the official opening – checking inventories, stocktaking, checking the sanitary condition, creating a computerised database (see previous section) – made it much easier for the curator to take on the daunting task of selecting the objects that would be included in the museum tour. Adding all this information to the collection database meant that detailed and precise lists could be made, relatively quickly.

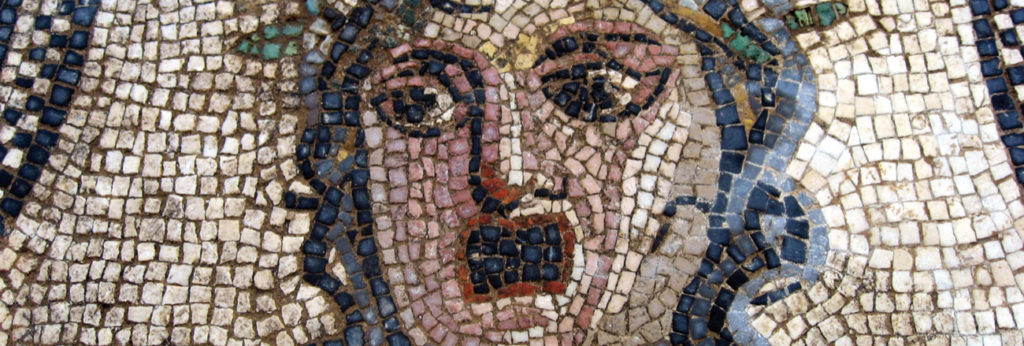

Around 2,000 objects were restored, including pieces made from stone, ceramic, glass, metal and organic materials (bone, cork, wood). It is interesting to highlight the great diversity of restored artworks: from the Augusteum pediment displayed in the atrium, weighing almost 20 tonnes, to the hair clips, weighing just a few grams.

RESEARCH

According to article 2d of the law of 2002, one of the ongoing missions of a Musée de France is to contribute to the progress made in knowledge and research, and in making it available to the public. Researching the collections and then making this research available to the public is one of the main objectives of the Musée de la Romanité.

The fact that the collections span so many different disciplines means that broad and varied knowledge is required, that the Conservation team alone, qualified in research, cannot cover completely. The museum team therefore needs to work in partnership with various other organisations: CNRS laboratories, Universities, INRAP, regional archaeology departments, restoration laboratories, colleagues from other museums, craftspeople specialised in ancient techniques, specialists in creating reconstitutions, local scholars, etc.

The work on an object begins with close observation and in producing a very detailed description. This is essential to be able to compare the objects with objects discovered on other sites or belonging to other collections. This means it can be identified and dated, and if it is in pieces, it can be restored to its initial condition.

The study also requires a report of the research already published (publications, articles, excavation reports, etc.) to be able to document these objects. This research includes data collected about its place of origin and where it has been moved to. All this detailed research leads to information about its purpose, its use and its original environment. The object cannot be studied alone, but in its archaeological and historic context.

The goal of the study and research is to then make this knowledge available to the general public. The most common ways of making the information available is by publishing it in the catalogues of the collections, by publishing articles in specialised journals and mainstream journals, conferences, and exhibitions with a published catalogue. Added to these traditional methods are the virtual methods using the museum’s website, the “Joconde” national database and specialised databases.

However, it is from within the museum itself, that the Visitor’s Department, a key service for the Musées de France, is responsible for passing on this knowledge directly to visitors during guided tours and educational workshops, as well as other events outside of the museum and during the biggest events of the year such as the Night of the Museums, European Heritage Days, and the European Archaeology Days.