The exhibition

A mortal among the Gods

From the Republic to the Empire

Octavian, great-nephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, reigned over Rome after a civil war in 31 BC, and skilfully imposed a new form of government, which appeared to respect Republican institutions: the Principate. Little by little, he monopolised the power of the majority of the traditional judiciaries, and him and his entourage eventually held all the political power in their hands. The honours that were bestowed upon him throughout his long political career, such as the nickname Augustus, granted him an aura of divinity, and he was considered to be more powerful than the average citizen. He therefore partly founded his power upon the sacred nature of his position. The worship of his qualities, virtues and actions was progressively incorporated into public religion, without changing the traditional view of religion, that Augustus continued to uphold. He would never be considered a God, and his living being would not be worshipped either in the Western world.

-

Paris, musée du Louvre. MA1276. -

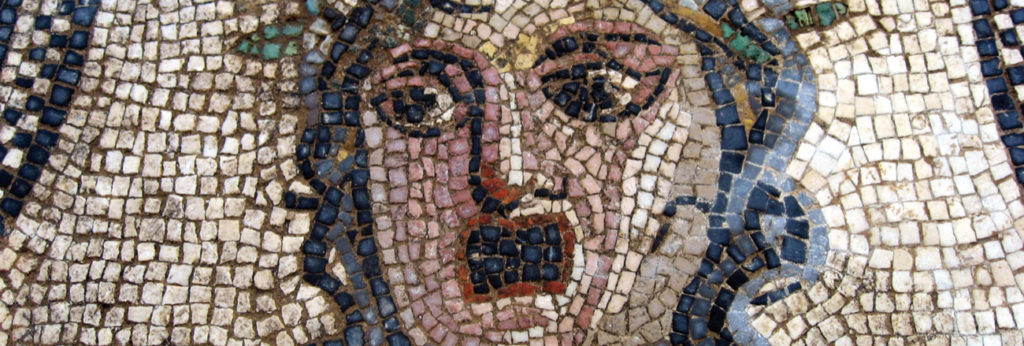

© C. Carrier, R. Gafà/Ville de Nîmes -

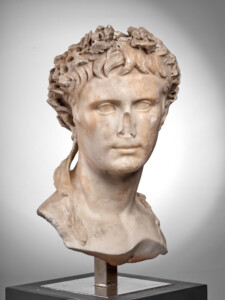

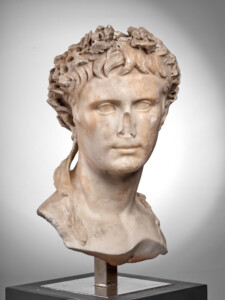

Buste d’Auguste couronné de chêne Marbre lychnites (île de Paros) Première moitié du Ier s. ap. J.-C. Martres-Tolosane (Haute-Garonne), villa de Chiragan Toulouse, musée Saint-Raymond

© Daniel Martin Fouinoflex

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

© C. Carrier, R. Gafà/Ville de Nîmes

The Emperor’s image

Throughout his reign, Augustus focussed on creating an image for himself, his family, and his political vision, that would legitimise his power and his actions. The ideology of this new regime was portrayed in different ways: through literature, coins and medals, sculpture, precious arts, etc. The various places and architectural monuments devoted to the celebration of imperialism (temples, sanctuaries, forums, theatres, etc.) served as the venue for the celebrations and events, centred around dynastic figures. At these venues, images of the prince and members of his family were surrounded by divinities, divine representations, mythical and religious references and decorative patterns of symbolic nature. When the portrait of the Emperor was installed in a public place, its presence brought with it protection and prosperity.

-

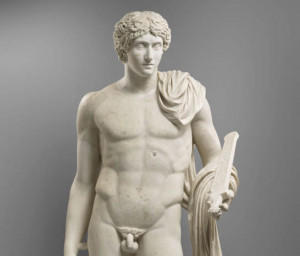

Statue de jeune homme Marbre Début du IIe s. ap. J.-C. (corps) ; années 170-180 (tête) Italie, Gabies. Ancienne collection Borghèse Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines -

Autel astrologique – marbre Époque impériale Italie, Gabies, 1792 Ancienne collection Borghèse Paris. Musée du Louvre, département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines -

Paris, musée du Louvre. MA683.

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Tony Querrec

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Tony Querrec

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

Divus Augustus

Augustus died on the 19th August 14 AD, at the age of 75. On the 17th September, a few days after his funeral, the Senate voted the honores caelestes, “heavenly honours”, which glorified him to a divine level (apotheosis in Greek). In Latin, this is called consecratio (the act of declaring something sacred). The prince was therefore granted the status of a secondary god, and became known as divus, but not deus, which was a term reserved for immortal gods. This consecratio came after a long line of official and spontaneous honours bestowed upon Augustus throughout his reign. This was a key political move because it guaranteed the transfer of power to Tiberius, stepson of the divine Augustus, in granting him legitimacy through divine ancestry. The consecratio of Augustus followed on from the apotheosis of Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, and the deification of Julius Caesar. This paved the way for the posthumous deification of most emperors and in rare cases, their family members, who would be honoured until the end of the Empire.

-

Paris, musée du Louvre. MA1239. -

Musée de la Romanité – Œuvres – Lampe à huile – M0455_007.1.72 -

Buste d’Auguste couronné de chêne Marbre lychnites (île de Paros) Première moitié du Ier s. ap. J.-C. Martres-Tolosane (Haute-Garonne), villa de Chiragan Toulouse, musée Saint-Raymond

S. Ramillon/Ville de Nîmes

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Tony Querrec

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

© L. Roux

Honouring the Emperor in Gallia Narbonensis

Public tributes

In Western provinces, and especially in Gaul, tributes to the imperial power were displays of political loyalty from local authorities looking to engage with the new administration. The central authority would encourage these initiatives before progressively granting local authorities with an institutional structure. Little by little, this act of worshipping the reigning prince, and the divi, emperors and members of the imperial family granted posthumous deification, would be structured and become official on various administrative levels, as a ‘cult’. In the West, the prince is not honoured alone, he is usually associated with the goddess Roma. Consequently, in the year 12 BC, this cult of Rome and Augustus was recognised on a federal level with the consecration of an altar in Lyon, the capital of the Three Gauls. At the provincial level, it was up to provincial assemblies to honour the emperor and the divi. Finally, at municipal level, the forms of the cult varied depending on the status of the town (colony, municipium or peregrinus towns).

-

Antonin le Pieux Marbre 138-161 ap. J.-C. Provenance inconnue, saisie révolutionnaire au château d’Ecouen en 1793 Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines -

Scène de sacrifice Marbre Dernier quart du IIe s. ap. J.-C. Ancienne collection Borghèse Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines -

Musée de la Romanité – Œuvres – Stèle funéraire – M0455_001.64.1

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

© S. Ramillon/Ville de Nîmes

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Anne Chauvet

© RMNGP/Franck RAUX

Private tributes

The discovery of imperial figures on private (houses, villas) and semi-private (company headquarters) property, combined with certain literary sources prove the existence of an individual devotion to the emperor. Individuals would pray for the pro salute (safety) of the head of State, who was responsible for ensuring peace and prosperity for the Empire. Roman poet Ovid for example, burned incense and prayed at his home before effigies of Augustus, Livia, and princes Tiberius, Germanicus and Drusus.

Additionally, iconographic themes featuring heroes or divinities imported from Greece by generals and political figures of the end of the Republic, then introduced into official art during the imperial era, were discovered in private dwellings, mainly as part of funerary decorations. This figurative language could be interpreted by anyone from the Roman society who was used to reading images and symbols.

-

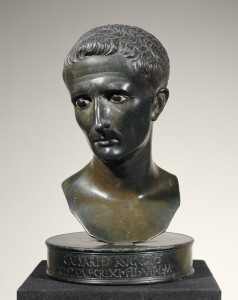

Paris, musée du Louvre. BR29. -

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, musée d’Archéologie nationale et Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. MAN77800. -

Paris, musée du Louvre. BR28.

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Gérard Blot

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Daniel Lebée/Carine Déambrosis

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Thierry Ollivier

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Archéologie nationale)/Franck Raux/Dominique Couto