The exhibition

The origins of the trojan war

To punish humanity for its sins and depopulate the Earth, Zeus, king of the Gods on Mount Olympus, plotted with his council Themis – goddess of Justice, Will and Divine Order – the events that would go on to trigger the Trojan War.

The epic tales of the Trojan War are based on factual historic events, but this battle is said to have taken place in a legendary era of the past, when the gods lived among people and heroes, in the same world.

‘For the Fairest’

The gods Zeus and Poseidon courted the Nereid Thetis, powerful goddess of water. When an oracle predicted she would give birth to a son who would be more powerful than his father, Zeus gave up Thetis and reluctantly handed her over to marry King Peleus. At their spectacular nuptials organised up on Mount Pelion, the gods brought the young bride and groom many gifts. Eris, goddess of strife and discord, was furious to have been excluded from the wedding, and decided to take revenge. She interrupted the banquet by tossing an apple inscribed ‘for the fairest’. The goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite all yearned for this title, but Zeus refused to choose between them. Therefore he ordered Hermes, messenger of the gods, to take them to Paris on Mount Ida (Anatolia, today’s Turkey), so that he would decide which of the goddesses was the fairest. Paris was believed to be the most handsome of men, with the purest of hearts.

Paris’ choice

Paris is one of the sons of Priam, King of Troy, and his wife Hecuba. Shortly before his birth, Hecuba had dreamt she gave birth to a torch that would set light to the city of Troy. This dream announced that her future child would be the cause of Troy’s ruin. When he was born, she abandoned the child on Mount Ida and a shepherd raised him. One day, when Paris was watching over the herds on Mount Ida, Athena, Hera and Aphrodite came to him, accompanied by Hermes. Sent by Zeus, they had come to resolve their dispute. In an effort to win, Athena promised him wisdom and victory, Hera, power over all Anatolia, and Aphrodite, the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen. In choosing Helen and taking her from her husband, the King of Sparta, Menelaus, Paris triggered the start of the Trojan War.

Achilles, the origins of a hero

The birth of Achilles

Seven children were born from the union of Peleus, a human, and the goddess Thetis. In an effort to make them immortal, Thetis gave them a treatment that killed them. Only the last born, Achilles, survived. There are two versions as to how Thetis attempted to remove the humanity from her son. One of the stories tells of how she exposed him to fire. Achilles was saved by his father and only a bone in his right foot was injured. Peleus’ protector, the centaur Chiron, was well-known for his talents in medicine, and he replaced this bone with that of Damysus, the fastest of all the giants. This could explain why Achilles was a particularly skilled runner and his legendary speed. The second version of this story tells how Thetis plunged her son into the river Styx, the river of the Underworld, believed to make those who swim there invincible. Thetis had been holding her son by his right ankle, and so it was the only part of his body not underwater, and therefore Achilles’ only vulnerable point.

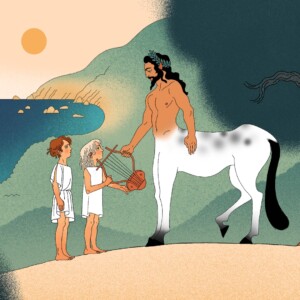

Chiron, Achilles’ educator

Achilles was the perfect embodiment of a hero: handsome, an excellent fighter, fiercely courageous. He was a talented lyre player and singer, and his melodies would calm any worries for both himself and his companions. He was aggressive and bad-tempered and liked to win. He was also known to be hospitable at times, even towards his enemies, and was a loyal friend. According to various versions of the myth, he was brought up either by his mother or by the centaur Chiron in his cave on Mount Pelion, along with his companion Patroclus. Chiron taught him the art of hunting and battle, music, morality and medicine. His education played a part in forging his physical talent, his knowledge and his moral values. This was what would have been expected according to the Greek concept of the ideal education, paideia. These educational ideals were based on the acquisition of literary, poetic, and scientific knowledge, as well as the practice of music and sports, in an effort to raise the ideal member of the Greek state, a well-rounded individual, refined in intellect, capable of following the laws of the polis and community living.

Achilles on Skyros

According to the prediction from the prophet Calchas, only Achilles’ participation in the Trojan War would lead the Greeks to victory, but it would also be the cause of his death. His mother, Thetis, decided to safeguard her son from this fate and as a child, she sent him to live on the island of Skyros, at the court of King Lycomedes. He was hidden in amongst the king’s daughters, and for many years he went by the name of ‘Pyrrha’ (the red-haired girl). He developed a relationship with one of the king’s daughters, Deidamia, and they had a son, Neoptolemus (also called Pyrrhus). The Greeks, having learnt of the prediction, sent Odysseus and Diomedes on a mission to Skyros to find Achilles and persuade him to take part in the upcoming battle. Odysseus used his famous trick to draw him out: he presented the king with a basket of gifts for his daughters, and hidden inside the basket were arms. When the trumpet alarm for battle sounded, Achilles, following his instinct, went for the arms and therefore revealed his real identity.

-

Le Styx – Anna Maria Riccobono pour Territorium.io -

Achille et Chiron – Anna Maria Riccobono pour Territorium.io -

Mosaique d’Achille à Skyros – Musée de la Romanité / Ville de Nîmes

Achilles and the trojan war

The choice of arms

On Skyros, Thetis gave Achilles the chance to choose his destiny: fight in the Trojan War and die young, or refuse to fight and live a long life. Despite his mother’s efforts to protect him, he chose his destiny. He chose an early death that came with eternal glory, as opposed to a long and happy life without any particular achievements or fame. He therefore joined the Greek army. This decision set in motion the final stage of his life. After a studious and peaceful childhood alongside Chiron, his teenage years spent protected within Lycomedes’ gynaeceum (women’s quarters), Achilles was introduced to an adult life and the world of battle. Achilles shone in battle and he led the Greek army thanks to his bravery and courage. He was the greatest of warriors and there was nobody like him on the planet. This is what forged the image and reputation of Achilles, as the ultimate hero and the absolute model of masculinity.

Action from the gods

The war between the Greeks and Trojans also divided the gods. Despite Zeus’ order not to intervene, they continued to influence human actions and demonstrated their preference for one side or the other. Hera and Athena, offended by Paris’ choice, supported the Greeks. Thetis wanted to protect and save her son. Hephaestus was loyal to Thetis and so made new arms for Achilles. Apollo, as founder of the ramparts of Troy, was the city’s protector. He infected the Greek camp with the plague, and directed Paris’ fatal arrow to Achilles’ heel. His twin sister Artemis decided to take his side. Aphrodite protected the romance between Paris and Helen, and Poseidon and Ares went from one side to another. Zeus, the supreme god, refused to take sides and would not support either party. He did not want to give any advantage to his children, his brother or his sister-in-law. In the duel between Achilles and Hector (heir to the Trojan throne), only destiny would decide upon their fate.

Achilles, the hero of the Trojan War

Achilles was fiercely opposed to Agamemnon, the most powerful of the kings and supreme leader of the Greek army, and he called his authority into question. He took offence when his war trophy, Briseis, was confiscated, and so he withdrew from battle. This caused a long period of defeat for the Greek army. Despite the promise of an extraordinary reward, Achilles refused to fight. In an effort to motivate the troops, his companion Patroclus put on Achilles’ armour and fought in his place. The trick was working, until Hector, son of Priam, killed him. Achilles was distraught and so he went back to battle and killed Hector. He took revenge by dragging Hector’s body around Troy, but then agreed to hand over the body to Priam who came to beg for it. During his last battle, he forced the Trojans to retreat back to their city but the arrow shot by Paris and guided by Apollo penetrated his only vulnerable body part, his heel. He died from his injury and so would never witness the fall of Troy. A fight broke out for the body of Achilles and it was Ajax the Great, who managed to recover the body.

16 major pieces

-

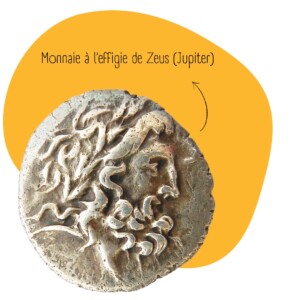

Drachma portraying Zeus (Jupiter)

Drachma portraying Zeus (Jupiter)

196- 146 BC. – Silver

Origin unknown – Nîmes, Musée de la RomanitéThe drachma was an official currency of Ancient Greece. The coin on display in the exhibition features Zeus (Jupiter), the king of the Greek gods. It is a profile representation, and he is wearing a crown of laurel leaves over his wavy, mid-length hair. This coin was minted by the town of Larissa in Thessalia, between 196 and 146 BC.

Its story

Zeus is at the origin of the Trojan War. Together with Themis, goddess of Justice, he decided to start a war between the Greeks and the Trojans, perhaps as a punishment for the population who had become too numerous and too arrogant. It was Eris, goddess of discord, who set this divine plan into motion. She wasn’t invited to Peleus and Thetis’ (the future parents of Achilles) nuptials, and so she took revenge by wreaking havoc between the goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite. She tossed a golden apple at their feet, intended ‘for the fairest’.

Photo © Ville de Nîmes / Musée de la Romanité

-

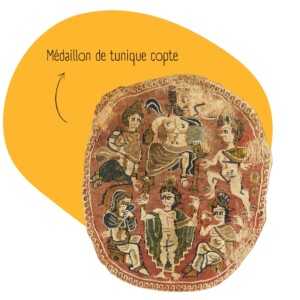

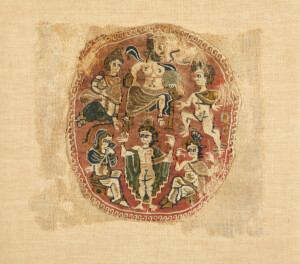

Sample of a Coptic tunic

Sample of a Coptic tunic

5th-6th century AD. – Linen and wool, hessian and tapestry

Antinoöpolis ? Amiens, Musée de PicardieThis piece of tunic (?) made from linen and wool represents Paris’ choice. It dates from the 5th-6th centuries AD and most likely comes from the town of Antinoöpolis in Egypt. There are six characters shown in two rows: on the top row is Zeus (Jupiter) sitting on a throne with Paris and Hermes standing alongside him, and on the bottom row is Hera (Junon), Aphrodite (Venus) and Athena (Minerva).

Its story

After being provoked by Eris, each of the three goddesses wanted to win the apple intended ‘for the fairest’. But Zeus refused to choose between them as he did not want to offend any of them. He decided that the decision would be made by Paris, a young shepherd who would take his sheep up to graze on Mount Ida, close to the wealthy and powerful city of Troy. Hermes, messenger of the gods, took the goddesses to him. Paris, who was actually one of Priam, king of Troy’s sons, chose Aphrodite. She promised to give him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world.

Photo © Alyx Taounza-Jeminet, Licence Ouverte via Wikimedia Commons

-

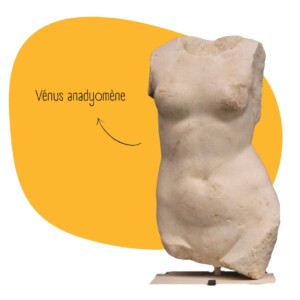

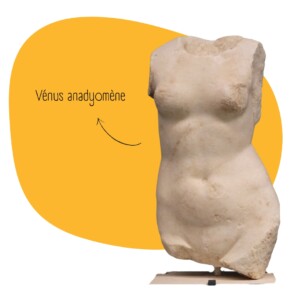

Venus of Nîmes

Venus of Nîmes

Léopold Mérignargues – 19th – 20th centuries

Plaster – Nîmes, Musée des Beaux-Arts, donation from the Mérignargues familyThis statue represents the goddess Aphrodite (Venus) getting out of a bath. She is naked and is holding her coat around her hips. This is a modern reproduction, in plaster, of a Roman statue that was discovered in Nîmes in 1873. This reproduction was created by the sculptor from Nîmes, Léopold Mérignargues.

Its story

Aphrodite is goddess of beauty, love and passion. During Peleus and Thetis’ nuptials, Eris, goddess of discord, tossed a golden apple at the feet of Aphrodite, Hera and Thetis inscribed ‘for the fairest’ and therefore started a competition between them. All the gods in attendance at the wedding, and Aphrodite herself, were convinced that she deserved the apple. But Athena and Hera also wanted the title of the fairest. It was decided that Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, would decide between them. He chose Aphrodite and the consequences of this choice would be deadly.

Photo © Cécile Carrier, Musée de la Romanité / Ville de Nîmes

-

Amphora portraying Helen between Achilles and Hector

Amphora portraying Helen between Achilles and Hector

520-510 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Bordeaux, Musée d’AquitaineThis Attic black-figure amphora portrays three of the main characters of the Trojan War: Helen, the woman for whom war was declared, Achilles, the most powerful of all the Greek warriors and Hector, the strongest of all the Trojan warriors. This piece dates from the late 6th century BC.

Its story

The most beautiful woman in the world, promised to Paris by Aphrodite, was Helen, King of Sparta, Menelaus’ wife. Paris was sent to Sparta on a diplomatic mission by his father, King Priam of Troy. He was given an honourable welcome from Menelaus, but when he saw Helen, it was love at first sight. Due to Aphrodite’s promise to Paris, Helen also fell in love with this Trojan prince and decided to leave with him. Taking advantage of Menelaus’ absence, Paris and Helen left together for Troy. When the king discovered his wife had fled, he decided to call upon his brother, Agamemnon, King of Mycenae and charismatic leader of the Greek kings. He decided to gather all the Greek troops to go and retrieve Helen from Troy.

Photo © Mairie de Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, photo L. Gauthier

-

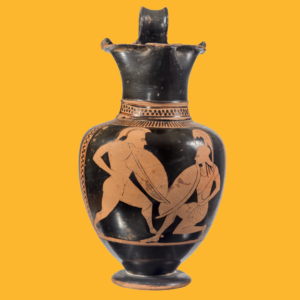

Hydria featuring Achilles and Ajax playing a game with dice or astragali

Hydria featuring Achilles and Ajax playing a game with dice or astragali

510 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Nîmes, Musée de la RomanitéThis Attic black-figure hydria (jug used to transport water) represents a game scene. The main characters are Achilles on the left and Ajax on the right. The two heroes are being watched by goddess Athena (Minerva) as they play. This vase dates from the late 6th century BC.

Its story

This episode does not feature in Iliad, nor in any other literary sources that speak of Troy. This scene is only represented on Attic black-figure vases. The two heroes are playing with dice or astragali (little bones). There are several hypotheses to explain the scene: it could be an illustration of a simple game while waiting to go to battle or a cleromancy (the art of reading the future) ritual the day before battle. Generally speaking, this appears to be a freeze frame illustrating soldiers in their free time. For the first nine years of the war, they had plenty of time for games.

Photo © Stéphane Ramillon / Ville de Nîmes / Musée de la Romanité

-

Sarcophagus of Achilles on Skyros

Sarcophagus of Achilles on Skyros

210-220 AD. – White marble

Origin unknown – Paris, Musée du Louvre, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquity

MNR (National Museums Recoveries register) artworkJust like the mosaic found in the excavation work on Avenue Jean-Jaurès, this lavishly decorated, embossed sarcophagus portrays the moment Achilles made his choice. Achilles is seen at the centre of the scene, removing his feminine garments that had hidden him, and picking up his arms. He is surrounded by the daughters of King Lycomedes, including Deidamia who is trying to hold him back, and by Odysseus and Diomedes. This sarcophagus is one of the artworks that was damaged during the Second World War. It is pending return to its lawful owners. It dates from the early 3rd century AD.

Its story

Odysseus and Diomedes were sent by Agamemnon to find Achilles and convince him to join the expedition to Troy. They knew he was hiding on Skyros, but Thetis had made him unrecognisable (dressed as a girl). Odysseus therefore came up with a way to encourage Achilles to reveal his true self. He and Diomedes went to the court of King Lycomedes with gifts for the king’s daughters. Hidden among the distaffs and bobbins for the daughters were arms. The king’s daughters were terrified when they saw these hidden objects, while Achilles could not resist the urge to pick them up. He had revealed his true self and then chose to face his destiny and join the Greek army.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / René-Gabriel Ojeda

-

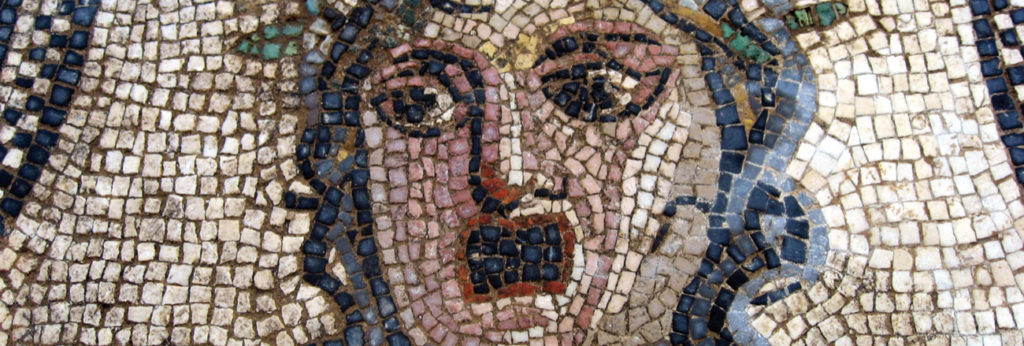

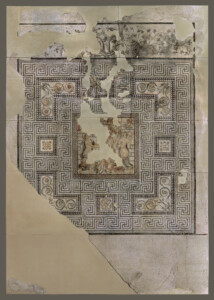

Mosaic of Achilles on Skyros

Mosaïque d’Achille à Skyros

150-200 AD. – Limestone, marble, glass, terracotta

Nîmes (30), Avenue Jean-Jaurès, 2007 – Nîmes, Musée de la RomanitéThis mosaic was discovered in Nîmes in 2007, during preventive excavation work on the Avenue Jean-Jaurès. The mosaics of Achilles and Pentheus were used to decorate two huge reception rooms in a large domus (urban house) The mosaic of Achilles represents the moment Odysseus unveiled Achilles and then his choice to leave the protection of the gynaeceum (women’s quarters) to face his heroic destiny. The character scene occupies the central part of a mosaic that covers the entire floor in the spacious reception room (53 m2) it was used to decorate. In the exhibition, only a part of the mosaic (36 m2) is on display. The mosaic was divided into several panels when it was restored, particularly to make it easier to handle. The mosaic dates from the second half of the 2nd century AD.

Its story

Thetis, Achilles’ mother, was aware that according to an oracle, her son Achilles was destined to die if he agreed to take part in the military expedition against Troy. Therefore, in an effort to protect him, she changed his identity (dressed him as a girl) and hid him in amongst the daughters of King Lycomedes at the gynaeceum on the island of Skyros. But the Greeks knew that without Achilles, they would lose the war with Troy. Odysseus and Diomedes were therefore sent on a mission to Skyros, and used a trick to unveil Achilles, causing him to choose to join the Greek army.

Photo © Ville de Nîmes / Musée de la Romanité

-

Cup featuring scenes from Achilles’ life

Cup featuring scenes from Achilles’ life

1100-1125 – Bronze

Origin unknown – Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Department of currency, medals and antiquesThis bronze cup is decorated all over with engraved character scenes. Seven scenes represent the key events of Achilles’ childhood. The arms and clothing are proof that this piece dates from the early 12th century and was made in the workshops of southern Italy.

Its story

Based on Achilleid, a poem written by Roman poet Statius in the late 1st century AD, the artist portrays some episodes of Achilles’ life:

- his arrival at Mount Pelion to be educated by the centaur Chiron,

- when his mother, Thetis, took him to the court of King Lycomedes on the island of Skyros, to protect him from his tragic and heroic destiny,

- when Odysseus found him and forced him to face his destiny,

- preparation to leave for battle,

- his proposal to Deidamia, King Lycomedes’ daughter, with whom he had a secret relationship,

- and finally, his departure by boat to fight in the war.

Photo © Bibliothèque nationale de France

-

Oenochoe representing Odysseus’ mission to find Achilles

Oenochoe representing Odysseus’ mission to find Achilles

550-500 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Department of currency, medals and antiquesThis Attic black-figure oenochoe (wine jug) represents the meeting between the two heroes in Achilles’ tent. Odysseus is sitting on a chair facing Achilles, also seated, with his coat wrapped around him. This jug dates from the second half of the 6th century BC.

Its story

In the tenth year of the conflict, Achilles refused to continue fighting as he was offended by Agamemnon who had taken his slave and war trophy, Briseis, away from him. He stayed in his tent and played the lyre. But his absence weakened the Greek army in the face of the Trojans. The situation got so bad that Agamemnon decided to send Odysseus, Ajax and Phoenix on a mission to try and convince Achilles to return to battle. Odysseus is represented here talking to Achilles, who is illustrated with a listless, sullen expression. This episode features in book 9 of Iliad.

Photo © Bibliothèque nationale de France

-

Mirror featuring Thetis handing Achilles his arms

Mirror featuring Thetis handing Achilles his arms

300 BC. – Bronze

Origin unknown – Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Department of currency, medals and antiquesThis Etruscan mirror is engraved with a scene illustrating the arming of a warrior. More specifically, it is the Nereid Thetis arming her son Achilles. This mirror dates from the 3rd century BC.

Its story

Following the death of Patroclus, Achilles decided to go back to battle to get revenge for his friend by killing Hector. But his arms had been taken from Patroclus’ body by the Trojans. His mother Thetis therefore asked the blacksmith god Hephaestus (Vulcan) to make him some new arms. He did so overnight. He made a shield with exceptional decoration. Thetis brought them to Achilles and helped him get ready for battle.

Photo © Serge Oboukhoff © BnF-CNRS-MSH Mondes

-

Oenochoe portraying the battle between Achilles and Hector

Oenochoe portraying the battle between Achilles and Hector

530-500 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Department of currency, medals and antiquesThis Attic black-figure oenochoe (wine jug) represents the final battle between Achilles and Hector. This piece dates from the late 6th century BC.

Its story

Following Patroclus’ death, Achilles returned to battle. He was consumed by his desire to get revenge. He wanted to fight and kill Hector in revenge for Patroclus’ death. In an effort to protect Hector, Apollo (protector of Troy) surrounded him in a thick cloud. But Hector was tricked by Athena (supporter of the Greeks) who impersonated his brother Deiphobus and promised to help him. Following a series of unavailing duels, Achilles finally came face-to-face with Hector. After an attempt to avoid going to battle with Achilles by fleeing around the walls of Troy, Hector decided to accept the battle. He was killed by Achilles.

Photo © Serge Oboukhoff © BnF-CNRS-MSH Mondes

-

Hydria representing Patroclus’ funeral

Hydria representing Patroclus’ funeral

520-480 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Nîmes, Musée de la RomanitéThis Attic black-figure hydria (jug to transport water) represents the games organised by Achilles for Patroclus’ funeral. The snake is a reference to the world of the dead. It is possible that this part was added when the jug was restored in the 19th century, to refer specifically to this episode of Iliad. This jug dates from between the late 6th century and the early 5th century BC.

Its story

Despite Odysseus, Ajax and Phoenix’s mission, Achilles still refused to go back to battle. The Greek army was in more and more difficulty and the Trojans had even managed to set fire to their ships. Faced with this desperate situation, Patroclus, Achilles’ dear companion, begged him to hand over his arms and let him fight alongside the Greeks. The Trojans would believe him to be Achilles and they would retreat out of fear. Achilles accepted but told him to be careful: he was to scare the Trojans but never venture as far as the city walls. But in the heat of the moment, Patroclus forgot the promise he had made to Achilles’ and approached Troy, fought Hector (prince and heir of Troy) who killed him, thinking he was Achilles. The Greeks managed to take Patroclus’ body back to the camp but the Trojans kept Achilles’ arms.

Photo © Ville de Nîmes / Musée de la Romanité

-

Copy of the mosaic illustrating Achilles dragging Hector’s body behind him

Copy of the mosaic illustrating Achilles dragging Hector’s body behind him

1846 – Paper

Nîmes, Carré d’Art library – Heritage collection, ms. 561A mosaic with an illustration in the centre of what Achilles subjected Hector’s body to was discovered in Nîmes in 1846. Louis Estève made the copy before the mosaic was removed from the location it was discovered in, therefore producing a reproduction that was faithful to the original setting. Unfortunately, when the mosaic was removed, using the technical means available at the time, most of the original decoration was destroyed.

Its story

After killing Hector, Achilles took his vengeance even further. He attached his enemy’s body by the feet to his chariot and dragged it around the walls of Troy. Hector’s parents, Priam and Hecuba, as well as his wife, Andromache, watched powerless as Achilles carried out this shameless act. Several days after his death, Achilles continued to drag Hector’s body around Patroclus’ tomb. Apollo, god and protector of Troy, prevented the body from getting too damaged.

Photo © Carré d’art bibliothèque – Ville de Nîmes

-

Amphora representing Ajax carrying Achilles’ body

Amphora representing Ajax carrying Achilles’ body

530-510 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Toulouse, Musée Saint-RaymondThis Attic black-figure amphora features an illustration of a warrior carrying a deceased battle companion. On either side of him is a man and a woman. This scene has been interpreted as Ajax carrying Achilles’ body, to take it to Thetis and Peleus.

Its story

Achilles was therefore killed by Paris. A battle ensued around his body and the Greeks managed to take it back to the camp, along with his arms. It was Ajax the Great, a warrior with considerable strength, who carried Achilles’ body on his back. A vigil was then held beside his body for seventeen days and seventeen nights before he was buried next to his companion, Patroclus.

Photo © Jean-François Peiré, CC BY-SA-NC-ND

-

Sarcophagus for Hector’s funeral

Sarcophagus for Hector’s funeral

190-200 AD. – White marble – Origin unknown

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman AntiquityThis fragment of a sarcophagus provides a realistic illustration of the moment when Hector’s body was taken back to Troy. The hero’s body features at the centre of the scene. Around the body are the members of his family: his parents Priam and Hecuba, his wife Andromache, their son Astyanax and his sister, the priestess Cassandra. This sarcophagus dates from the late 2nd century AD.

Its story

The way Achilles’ treated the deceased was unacceptable for the gods. They intervened, sending Priam to Achilles to ask him to return his son’s body, so he could give him the funeral he deserved. Priam therefore made his way to the Greek camp and went to Achilles’ tent carrying riches to exchange. Achilles pitied the suffering of this man before him and also respected him because he had risked his life by venturing into the enemy camp. He handed over Hector’s body to him.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / image RMN-GP

-

Fragment of a vase illustrating Paris shooting an arrow through Achilles’ heel

Fragment of a vase illustrating Paris shooting an arrow through Achilles’ heel

Around 550 BC. – Terracotta

Origin unknown – Toulouse, Musée Saint-RaymondThis fragment of an Attic, black-figure vase represents a battle scene which was interpreted as the moment when Paris injuries Achilles in the heel. This vase dates from around the middle of the 6th century BC.

Its story

Achilles was the son of Peleus, a human, and the goddess Thetis. When he was born, his mother plunged him into the waters of the river Styx, the river of the Underworld, in an effort to make him immortal. In doing so, she was holding him by the foot and only the child’s right heel remained out of the water. This body part was therefore Achilles’ only weak point. After the death of his brother Hector, Paris killed Achilles with an arrow that was guided into his heel with the help of the god Apollo. There are several versions of this story: that Paris shot the arrow at Achilles from the top of the city walls of Troy, and that he threw a spear at him on the battlefield. This last version is portrayed on this vase.

Photo © Alyx Taounza-Jeminet, Licence Ouverte via Wikimedia Commons