The exhibition “Gaulish but Roman! Masterpieces from the National Archaeology Museum”

Getting out of the Gallic forest

“Gallia Comata” refers to independent Gaul before its subjugation by Julius Caesar. It was located to the north of the Roman province that would later become Narbonne. The adjective comata means “hairy” or “long-haired”. Among the representations of “Hairy Gaul”, the image of a wild territory, covered in forests and inhabited by wild boars, has become a widespread cliché in literature.

However, archaeology has challenged the idea of impenetrable forests. Contrary to popular belief, the Gauls were not a woodland people living in huts deep in the woods. This vast territory, stretching as far west and north as the ocean and as far east as the Rhine and the Alps, was cultivated. According to the traditional view, Julius Caesar’s conquest of hairy Gaul was followed by extensive deforestation by the Romans. However, this idea needs to be qualified: the development of the land and landscapes bears witness to an acculturation, to an area that was both Gallic and Roman (woods, groves, villae, communication routes, towns, sanctuaries, etc.).

Inhabiting the forests, the wild boar is both a totemic animal and a noble game species. It appears on Gaulish coins and Celtic weaponry. Prominently featured in Celtic mythology, the boar forms connections with the divine realm. It is also found among the motifs of religious sculpture. In the Greek and Roman worlds, it was seen as dangerous and aggressive game, whose capture was considered heroic: “I see it bristling its hairs, throwing fire from its eyes; I hear the sound of its teeth as it sharpens them against you” (Philocrates, Imagines, 28.1).

Fulmen habent acres in aduncis dentibus apri1 (Ovide, Métamorphoses, X, 550)

For the Romans, the wild boar was an excellent game animal, second only to the lion. Hunters were as wary of male boars as they were of cows defending their young. Facing the boar was, in a way, facing death, from which greatness is born.

Gallo-Roman society

After the Roman conquest, especially during the first century, a new social system based on the Roman model was established. Free men lived alongside slaves, freedmen, and others. Some were Gauls, while others came from Italy or other provinces of the Empire. Some were citizens who pursued political careers, while others were merchants, craftsmen, soldiers, teachers, doctors, and priests. This section provides portraits of the inhabitants of the Gallic provinces according to their place in society rather than from a geographical point of view.

Citizens and elites

Caesar granted Roman citizenship to many Gauls. The study of family names (onomastics) reveals the Latinisation of former Celtic names. Among Roman citizens, we find the rise of provincial and municipal elites, comparable to a wealthy upper middle class. These exceptional citizens, with their personal wealth, gained access to the highest political and administrative positions. There are many examples of these provincial elites, including inscriptions and statuary. Certain objects and cultural practices bear witness to their involvement in the public and economic life of their cities.

The Roman Army in Gaul

Contrary to what the adventures of Asterix would have you believe, the presence of the Roman army in Gaul was not always synonymous with conflict. Once the conquest was over and the Pax Romana (Roman peace) had been established, soldiers remained in place. They could be employed on control missions, such as quarrying, waterworks and minting coins. Like all subjects of the Empire, Gallo-Romans were obliged to undertake military service. Roman citizens were required to serve for twenty years in the legions, while peregrines (free men without citizenship) had to serve for twenty-five years in the auxiliary troops. Evidence of the Roman army’s presence can be seen in the many inscriptions, weapons and soldiers’ graves that have been discovered.

Slaves and freedmen

Ancient societies were servile societies. Although they were numerous, slaves are not very visible in historical and archaeological evidence. Evidence of their presence is usually limited to a few examples of iron shackles, used not only to restrain slaves, but also prisoners or even animals. Manumission was the only way out for a slave, as a master could grant freedom. Freedmen living and working in Gaul sometimes came from the eastern provinces of the Empire. Some managed to rise to the status of local notables and amass significant wealth, though they were not always fully recognised as citizens or allowed to hold political office. However, they could take on religious roles or responsibilities within professional associations (collegia).

People of Trades

In Roman Gaul, a significant number of funerary stelae depict the deceased holding their tools or practising their trade. Blacksmiths, clog makers, pit sawyers, drapers, fullers, painters, butchers, and shopkeepers are shown at work, while others are known through the names they left inscribed on their tools.

Living the Roman Way in Gaul: Between Town and Countryside

Land use in Roman Gaul was organised around a network of roads, towns (chief towns and secondary settlements) and rural settlements. The farms and villas scattered throughout the region were vast establishments, typically covering two or three hectares and housing several dozen people. This type of settlement dominated the Gallo-Roman countryside and followed a pattern established during the Gallic Independence period with the ‘native farms’. Here, local traditions reinforced the new trends brought about by Romanisation. However, recent research shows that many Gallo-Roman rural settlements were established as new creations from the early 1st century onwards, albeit at different rates in different regions. Often, these villas were destroyed, sometimes deliberately, after which they were levelled and their materials salvaged. Photo-interpretation and geophysical techniques can be used to identify their layouts. In Lyonnais Gaul and Belgium, the most common design features a long building with a gallery at the front (open to the farmyard), which is often flanked by two corner pavilions. The residential area (pars urbana) extends behind the gallery.

The Gallo-Roman villa of La Millière is renowned for its remarkable wall paintings, discovered during excavations carried out between 1977 and 1980 by amateur archaeologist F. Zuber. These frescoes, consisting of numerous fragments found either on the ground or still attached to the walls, were carefully studied and reassembled in 2021 and 2022 by specialists from the Centre for the Study of Roman Wall Paintings in Soissons. This detailed analysis made it possible to reconstruct the villa’s full decorative scheme.

The “Four Seasons” decoration comes from a small private room located in the north-west part of the villa. Built in the 2nd century, the room was refurbished in the early 3rd century with a hypocaust heating system, an alcove, and two vaulted ceilings—features that reflect the social status of the owner. The walls were adorned with painted imitations of marble in the lower section, topped with a stucco cornice, while the upper part was divided into panels decorated with garlands. The groin vault, the best-preserved of its kind in Gaul, features four painted hexagonal medallions, each depicting an allegory of one of the seasons. While Spring and Summer follow conventional representations, Autumn and Winter depart from the usual iconography. This refined décor, combining painting and stucco, highlights the villa’s connection to the agricultural cycle of the seasons.*The restoration work was supported by Crédit Agricole d’Ile-de-France Mécénat and the Fondation Crédit Agricole – Pays de France.

The Domain of the Gods

The Gallo-Roman patheon

Before Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, the Gauls had a rich and complex pantheon. Gallo-Roman representations provide us with some images and some names, proving that these gods continued to be venerated alongside the new Roman gods. The combination of Gallic and Roman gods, which blends the integration of Roman religion with loyalty to native cults, is a symbol of Romanisation.

The Gallo-Roman collection at the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale is made up of numerous divine representations in a variety of sizes and materials (limestone, marble, copper alloys, terracotta, etc.), and bears witness to the vast number of deities in the Gallo-Roman pantheon and the diversity of their images.

Religious practices

Archaeological excavations were carried out at La-Croix-Saint-Charles in Alise-Sainte-Reine (Côte-d’Or) by Émile Espérandieu (1909-1911). Numerous offerings representing parts of the human body (knee, trunk, eyes) and several representations of babies swaddled in swaddling clothes were offered to the god Apollo Moritasgus.

Émile Espérandieu is no stranger to Nîmes. A soldier, epigraphist and archaeologist, he came from Saint-Hippolyte-de-Caton in the Gard department. He made a name for himself in the world of archaeology by studying and publishing the stone sculpture of Gaul in collections that still bear his name, before becoming director of the Alesia excavations in 1906. In 1918, he retired to Nîmes, where he became curator of ancient monuments and archaeological museums. He was also a member of the Académie de Nîmes and its École Antique.

The invention of Gallo-Roman archaeology

Napoleon III and Roman Gaul

Napoleon III had a passion for Julius Caesar, Roman history and archaeology. Anxious to reconcile the French, who until then had been divided by their national origins, Napoleon III sought to create a Gallo-Roman France that would transcend the clashes of memory. The excavations at Alesia led to the founding of the Gallo-Roman Museum in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the former castle of the kings of France, on 8 March 1862. This museum played a part in the institutionalisation of archaeology and its development as a scientific discipline, and contributed to the edification of the citizen through its educational vision and its demand for transmission. When the museum opened in May 1867, only the Salle d’Alésia, recounting the Roman victory over the Gauls, was inaugurated. Twenty or so other Gallo-Roman rooms were subsequently opened before the 1914 war. Hairy Gaul was at the heart of republican thinking: on the one hand, the hairy, sylvan Gauls with their simple, frustrated lifestyle; on the other, the Romans who embodied administration, order, organisation and rectitude in all things.

The trauma of the 1870 military defeat at the hands of Prussia led to an explicit parallel with Vercingetorix’s defeat by Julius Caesar at Alesia in 52 B.C. This comparison served to highlight the Gallic hero and the urgent need to learn from his conqueror. As Gaul, conquered by Rome, had become a brilliant civilised province, France, defeated by Prussia, had to reform itself by drawing inspiration from the effective methods of its conqueror. Thus, to be ancient and legitimate, France had to be Gallic, but to be civilised and civilising, it had to be Roman. In other words, France must be Gallo-Roman.

The archaeology of Roman Gaul, from the treasures to the site

In our collective imagination, the word ‘treasure’ evokes images of rare and unique objects. It refers to a collection of precious materials (such as gold, silver and jewels) that have been accumulated and often carefully hidden away. Sometimes these treasures have been hidden away and forgotten, with the owners unable to recover them. This presentation explores the rapid recognition of the scientific interest of these ‘treasures’ for archaeology. While these objects are exceptional and made from precious materials, their discovery and study by archaeologists reveals a great deal about the historical context in which they were hidden. Most of their burials date from the 3rd century, a period marked by major upheavals within the Roman Empire.

This period, long known as the Late Roman Empire and more recently as Late Antiquity, was a complex time that marked the beginning of the organisation of the medieval West. The emergence of new centres of political, economic, intellectual and religious power led to great instability, with a succession of puppet emperors and usurpers, a military threat on the borders of the Empire, an economic crisis shaken by currency devaluations, a religious upheaval during which Christianity replaced polytheism as the official religion, climatic changes and so on. This context alone justifies the fact that some people tried to protect their valuables and cash by burying them in the ground in the hope of one day recovering them.

Some of these treasures have been found by chance long afterwards. But beware! Treasure hunting is an illegal activity. Operating with a metal detector (“frying pan”), these prospectors plunder archaeological sites, depriving archaeologists of essential knowledge for understanding the remains, and museum visitors of priceless heritage. Treasure hunters face fines of up to €100,000 and seven years’ imprisonment.

These treasures are important reminders of our history, our resilience, and our collective responsibility to preserve this heritage for future generations.

Also in the exhibition…

Fashions and dress codes in Roman Gaul

As part of the textile and denim events organised in Nîmes in 2025, the ‘Gauls, but Romans’ exhibition offers an exploration of Roman Gaulish costume.

Among the objects generously loaned by the National Archaeology Museum are representations of men, women, children and deities of Greek, Roman and Gaulish origin, which give an idea of the variety of clothing worn at the time. While each group had its own distinctive style, external influences constantly blended styles and techniques, resulting in fashions that fluctuated as much as those of today.

However, in the highly hierarchical Roman society, dress codes were based on gender, social status, function and context. Clothing was a means of identifying the person wearing it. These dress codes were applied throughout the Empire, although traditional local dress was not completely abandoned, with some even being adopted by the Romans.

This tour covers 20 works in the exhibition.

15 Major Works

-

Sculpture of a character with a boar

Sculpture of a character with a boar

Limestone; h. 25.8; L. 10.5 cm Late 2nd-1st century BC Euffigneix, La Côte d’Alun (Haute-Marne) Purchased 1946; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This fragment of sculpted relief, discovered in the 1920s during agricultural work, had been deposited in a “pit filled with bones.” It depicts a male figure, of whom only the torso and bowed head are preserved, wearing a tubular torque with decorated terminals. A large boar, with its crest raised, appears in the background at chest level.

The man, without arms, appears to be an apparition. On the left, a huge eye, possibly animal, is visible, while on the right, very fragmented, another animal figure seems to be represented.

The back and top of the head, topped with a catogan and long locks of hair, have been torn off. No associated furniture was found. The torque is reminiscent of examples in gold plate from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The scene remains enigmatic: the man could be an ancestor hero rather than a deity, while the boar underlines the links between humans and animals, endowed with spirit and power.

Photo : @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

Laie de Cahors

Laie de Cahors

Copper alloy; h. 21.6; L. 37; D. 10.4 cm 2nd c. AD?; Cahors (Lot) Purchase 1872; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This bronze sculpture, unearthed in 1872 in Cahors along with the foot of a large statue, comes from a site containing columns, capitals and mosaics, probably a notable’s house, a public building or a sanctuary. Located in Divona Cadurcorum, capital of the Cadurques, the ancient city covered almost 200 hectares at its peak.

The goose, remarkable for its size and realism, is depicted in motion, in a defensive posture: hind legs outstretched, udders visible, snout elongated, mouth open to reveal its tusks. Its crest and fur are finely incised in the metal. An emblematic animal of the Celts, the boar also appeared in Greco-Roman art, often in hunting scenes, as on a sarcophagus discovered in Saint-Béat.

Realistic and influenced by Hellenistic art, this sculpture is reminiscent of other similar works produced in Roman Gaul in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

Photo : @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

Funerary stele of Julia Paullina

Funerary stele of Julia Paullina

Shell limestone; h. 142; L. 68.5; D. 33 cm. 3rd c. AD ?; Bourges (Cher), Fondation du Séminaire de Bourges, rue Moyenne Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

Avaricum (Bourges), the capital of the Bituriges Cubes, was an important city in Antiquity, surrounded by numerous necropolises. The funerary stele of Julia Paullina was discovered in 1704 during the construction of the seminary.

It features a large triangular pediment with acroteria decorated with palmettes. In the centre of the tympanum, the inscription D.M. is engraved, followed by a dedication: ‘To the spirits and memory of Julia Paullina, his wife of 50 years, Tenatius Martinus (erected this monument)’.

The sides of the stele, decorated with draperies and various objects such as a casket, sandals and a comb, feature a unique decoration whose symbolism remains enigmatic. The quality and originality of this sculpture bear witness to refined craftsmanship.

Photo : @ MAN / Baptiste Simon

-

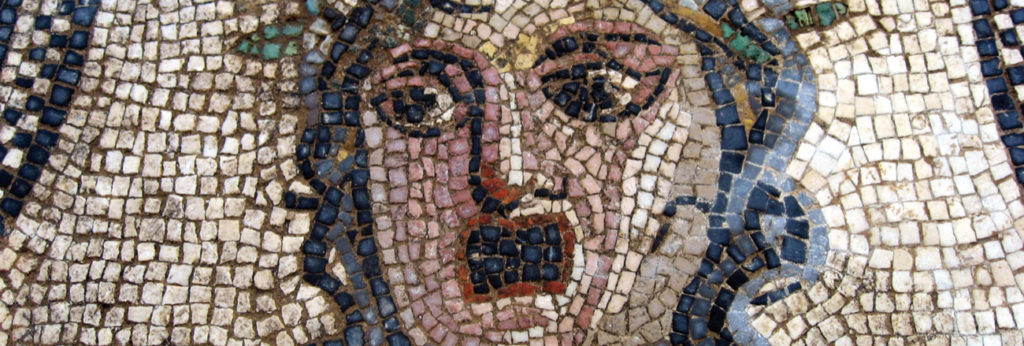

Face mask visor from a cavalry helmet

Face mask visor from a cavalry helmet

h. 19; L. 19.5; W. 15.5 cm; 1st century AD Conflans-en-Jarnisy (Meurthe-et-Moselle) Purchase 2019; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

Discovered in Conflans-en-Jarnisy, near Metz, the capital of the Médiomatriques city, the visor bears witness to the Roman military presence in a buffer zone. Used for parades and training, these visors, dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries, were used to impress opponents.

This young man’s face hammered out of copper sheet is the removable visor from a Roman ‘face helmet’. The top of the forehead and the temples are adorned with a crown of two intertwined plant oaths. A large gap in the right eye and a slight deformation in the width of the face do not detract from the object’s aesthetic quality. The powerful nose extends from a narrow, flat forehead, defined by angular superciliary arches above almond-shaped eyes with slightly lowered eyelids. The half-open mouth with its thick lips and rounded chin add a touch of humanity to the idealized Hellenistic features of the whole. A small flat-headed pin made of copper alloy, near the bottom right-hand side edge, whose symmetrical counterpart has disappeared, is part of the system used to attach the visor to the stamp. On the top of both ears, traces of iron oxide seem to prove that this, which has disappeared, was made of iron.

Photo : @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

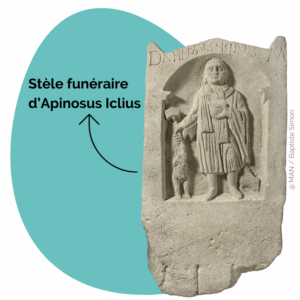

Funerary stele of Apinosus Iclius

Funerary stele of Apinosus Iclius

Limestone; h.110 ; l.60 ; w.20 cm; 2nd century AD Entrains-sur-Nohain (Nièvre) Purchase 1909; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This stele, discovered in 1860 during work on a tile factory, has remained intact. It marked the site of a grave, probably a pit containing a cinerary urn and offerings such as jugs and jars. Found in a necropolis near Entrains-sur-Nohain (known as Intaranum in Antiquity), it was located near roads linking Intaranum to Cenabum (Orléans) and Avaricum (Bourges).

Photo : @ MAN / Baptiste Simon

-

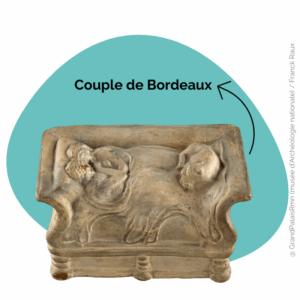

Couple from Bordeaux

Couple from Bordeaux

Terracotta; h. 6.3; l. 7; w. 12 cm Late 2nd-early 3rd century AD; Bordeaux Donation 1925; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This terracotta, discovered in 1851 during the excavation of a house in Bordeaux, known in antiquity as Burdigala, remains in an uncertain context: a dwelling, a tomb, a sanctuary? Burdigala, founded in the Iron Age, became the administrative capital of Aquitaine and a major port under Vespasian (69-76).

This sculpture features a bed of considerable proportions, with high uprights resting on legs reminiscent of Roman turned-wood models. Under a blanket, a couple rest on a mattress and bolster. The woman, identifiable by her long hair, is embracing the man, and a finely detailed dog lies at their feet. The work bears the inscription Pistillus fecit (‘Pistillus made’), attributing the sculpture to the Pistillus dispensary, one of the most important in Roman Gaul. Less expensive than stone and bronze sculptures, these terracottas were actively traded.

Photo : @ GrandPalaisRmn (National Archaeology Museum) / Franck Raux

-

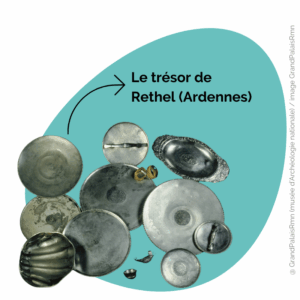

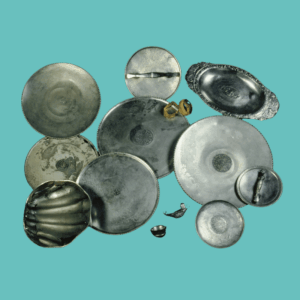

The Rethel treasure (Ardennes)

The Rethel treasure (Ardennes)

Late 2nd – first half of 3rd c. Gold (bracelet) and silver Oval dish: L.51.2, W.21.7 cm. Purchased 1985; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

The Rethel treasure was discovered in 1980 during a clandestine excavation near an ancient Gallo-Roman villa. Part of the treasure was offered to the Louvre Museum. Following an administrative investigation lasting several years, the owner of the land was recognised as the sole owner of the objects. Part of the treasure was purchased from her by the State in 1983, while another part was dated to the public collections in 1986.

The treasure represents a silver weight of almost 20 kg. The fifteen objects that make up the treasure were wrapped in cloth and placed in a vast bronze basin, which has now been almost completely destroyed. As is often the case, the treasure includes jewellery, toiletries (two mirrors and at least one of the shell-shaped basins) and tableware.

Among the latter, drinking vessels are almost completely absent, reflecting a characteristic of 3rd-century silver services. The decoration of nielloed rosettes on several dishes was also fashionable throughout the 3rd century. The Rethel treasure is just one in a long series of discoveries that identify very active silversmiths in Gaul itself.

Photo : @ GrandPalaisRmn (National Archaeology Museum) / image GrandPalaisRmn

-

The Four Seasons at the Villa de La Millière: Summer

The Four Seasons at the Villa de La Millière: Summer

Limestone and pigments of various origins; 3rd century AD La Millière, Les Mesnuls (Yvelines) Purchase 2023; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

The Gallo-Roman villa at La Millière in Les Mesnuls (Yvelines) is known thanks to the discovery of exceptional wall paintings during excavations carried out between 1977 and 1980 by F. Zuber, an amateur archaeologist. These frescoes represent a large number of fragments, collapsed on the floors or sometimes still in place on the walls. In 2021 and 2022, archaeologists and toïchographers from the Centre d’étude des peintures murales romaines de Soissons (Soissons Centre for the Study of Roman Wall Paintings) carried out a long and meticulous process of observation and reassembly. This exhaustive study has brought to light the entire villa’s ornamental programme, which had long been left in the shadows.

The decoration for the Four Seasons comes from a small room in the north-west corner of the villa, in the area considered to be the owners’ private flats. Although the villa was built in the early 2nd century, it was during the first half of the 3rd century, during the villa’s second decorative phase, that this room was fitted out with a hypocaust heating system. Featuring an alcove and two vaulted ceilings, this room reveals the owner’s desire to create a special setting, in vogue in the homes of the elite of the period, revealing his social status. The lower walls were decorated with imitation marble, crowned by a stucco cornice. Higher up, the white field is divided into panels by columns bordered by upright garlands.

The cross vault that crowns the main space is the best preserved in Gaul. Four hexagonal medallions are painted on it. Each contains a bust of a figure representing the allegories of the Seasons. Each is dressed in a simple tunic and wearing a plant crown. Alternating between red and green, they are framed by a frieze of festooned hangings.

Summer, in a green medallion, is conventionally depicted with ears of wheat. She is dressed in a green tunic and wears her hair short, evoking a masculine figure.

Photo : @ APPA CEPMR / JF Lefevre

-

Cross-legged seated deity

Cross-legged seated deity

Copper alloy, glass paste h. 41.5 ; L. 22 ; pr. 17.5 cm Late 1st century BC – Early 1st century AD ? Bouray-sur-Juine (Essonne) Purchase 1933; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

It was during the dredging of the river running through the grounds of the Château du Mesnil-Voysin (Essonne) that this statue was brought to light. Many years later, Antoine Héron de Villefosse—an eminent member of the Commission Topographique des Gaules—became aware of the discovery, which he reported in 1911 to the Société nationale des antiquaires de France. In his description of the object, the archaeologist mentioned the yellow colouring of the copper, which is consistent with an item that had remained submerged in water for an extended period. In 1933, the heirs of the Marquise d’Argentré permitted its acquisition by the National Museum of Antiquities.

The description of the object provided by Héron de Villefosse offers valuable information about its state of preservation at the beginning of the 20th century. The upper part, corresponding to the head and neck, is made of two moulded sheets of metal, which are therefore thicker than the other parts of the body, which are made of hammered bronze sheet. The back is unsealed. The torso and the folded legs of the figure consist of two sheets welded together, with the junction concealed by small brass tabs. These tabs have been torn away on the right side, and a copper clasp appears to have been used as a repair attempt. The head, disproportionately large in relation to the rest of the body, has eye sockets. The left socket retains a white and cobalt blue glass paste eye for the pupil. As for the now-missing hands, it is likely that they rested on the figure’s knees, as the traces still visible strongly suggest. The absence of any marks on the torso indicates that the arms may have been spread out, similar to the figurine from Glauberg (Germany).

Photo : @ MAN / Baptiste Simon

-

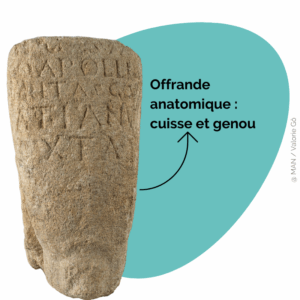

Anatomical offering: thigh and knee

Anatomical offering: thigh and knee

Limestone; h. 33, l. 29 cm. 2nd half of 2nd c. or early 3rd c. AD. Alise-Sainte-Reine, lieu-dit “La Croix Saint-Charles” (Côte-d’Or) Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This partial representation of the human body, made of soft limestone, depicts a thigh up to the knee, the latter emphasised by a bulge of flesh above it. The upper part of the sculpture is flat, and the back of the thigh rests against an element, the interpretation of which has varied according to É. Espérandieu, who discovered the object in 1910. In his excavation report, he saw “a dolphin on the left side and foliage behind.” Fifteen years later, in volume 9 of his Recueil général de la statuaire en Gaule romaine, he no longer saw a dolphin, but “large buds on the surface of a wound.” The clearly visible fins and the undulating fish-like body suggest that the first interpretation should be revisited. On the anterior bulge of the thigh is incised a dedication in five lines, the first almost erased: “Aug(usto) sac(rum) deo Apollini Moritasgo Catianus Oxtai”, which translates as “Catianus, son of Oxtaus, dedicated this offering to the god Apollo Moritasgus Augustus” (CIL 13, 11240). Noteworthy are the Gallic names of the donor and his father, as well as the use of a dedication formula typical of the Aeduan tribe, to which Alésia is linked, likely since 69 CE (the object itself is probably dated to the second half of the 2nd century or the beginning of the following century). Anatomical offerings, common in the Greco-Roman world, spread throughout Gaul after the conquest. They represent all possible parts of the body: torsos, limbs, internal and external organs. Knees are a frequent form, for example, at Halatte and the Sources of the Seine. They sometimes carry dedications, such as those found at Alésia itself or at Essarois, where Apollo was also venerated but under a different Celtic epithet (Apollo Vindonnus: CIL 13, 5646). In Alise-Sainte-Reine, the existence of an Apollo Moritasgus was known since the 17th century through the discovery of a reused inscription, now lost. However, it was not until 1910 that É. Espérandieu, thanks to the dedication of Catianus and another from a certain Diofanes on a stone trunk, understood that the spring sanctuary he was excavating was dedicated to Apollo Moritasgus. Since the resumption of excavations in 2008, three new dedications to Moritasgus have been added to those already known. These undoubtedly confirm the identity of the deity worshipped at the site. Discoveries of anatomical ex-votos, in limestone or bronze sheet, have also multiplied there.

Photo: @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

Mercury with a sickle

Mercury with a sickle

Shell limestone; h. 70; l. 25; w. 14.5 cm 2nd c. AD ? Morienval, La Carrière-du-Roi (Oise) Gift 1884; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

Between 1860 and 1870, Albert de Roucy, a judge in Compiègne, was entrusted by Napoleon III with a “special archaeological mission” aimed at exploring the forest adjacent to the emperor’s château. Discovered in 1871, this small sculpture, simplified and distant from Greco-Roman canons, evokes Gallic traditions and raises questions about the role and perception of Mercury in Gallic society.

Photo: @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

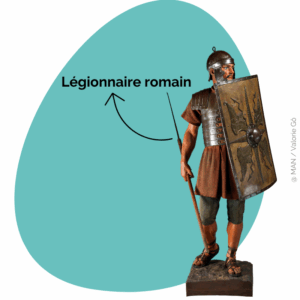

Roman legionary

Roman legionary

Auguste Bartholdi (1834-1904) 1870; Wood, plaster and textile. Donated by Emperor Napoleon III to the Musée d’Archéologie nationale, 1870 Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

When the National Museum of Antiquities opened, Napoleon III commissioned Auguste Bartholdi, the creator of the Statue of Liberty, to create a mannequin of a Roman legionary, symbolising the military power and organisation of the Roman Empire. Bartholdi was inspired by the bas-reliefs on Trajan’s Column to design this plaster statue, depicted with a pilum (throwing spear). The leather caliga discovered in 1857 at Mainz served as the model for the soldier’s footwear, while the original is displayed in a case at the soldier’s feet.

Photo: @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

Alésia Drinking Vessel

Alésia Drinking Vessel

Silver and gilding; h. 11.5; d: 11; w: 18.8 cm First half of 1st century BC Donated by Emperor Napoleon III to the Musée d’Archéologie nationale, 1867 Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

This vase was discovered in 1862 in a ditch of the fortifications built by Caesar at Alésia, during excavations led by Napoleon III. Sent to the emperor by Commander Stoffel, it was quickly presented in the newspapers as having belonged to Caesar, thus becoming a symbol of Napoleon III’s archaeological endeavours. In reality, it is a luxurious cup typical of Roman silverware services. An inscription references a missing twin cup, while a Greek name and the profession “goldsmith” are engraved.

Another inscription may indicate a Gallic ritual use. This vase attests to exchanges between Mediterranean and Gallic cultures, having passed through aristocrats or merchants before being offered in a sanctuary and later abandoned under unknown circumstances.

Photo: @ MAN / Valorie Gô

-

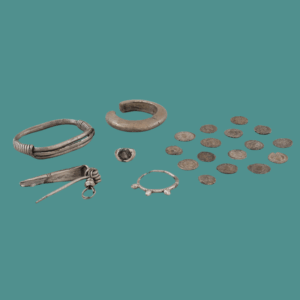

The Donzacq Treasure

The Donzacq Treasure

Silver; 2nd half of 3rd century AD Donzacq (Landes) Purchase 1873; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

The hoard of coins and jewellery discovered in 1866 at Donzacq (Landes) was sold in 1873 by the Lavigne sisters, owners of the land where the discovery was made, through the intermediary of R. Pottier, a local collector. It comprises 16 denarii and antoniniani (inv. 20043), silver and billon coins, as well as two bracelets, an earring, a ring, and a silver fibula (inv. 20038 to 20041). It is worth noting that the Musée d’Archéologie nationale originally received 67 coins but chose to keep only sixteen—“one of each emperor” represented in the group handed over.

The hoard, the precise date of which is not known, originally contained around 1,200 coins and about ten silver items of jewellery, the latter wrapped in fabric. It had been placed in a pot, which was broken, and no shards were preserved. Three of the pieces of jewellery were purchased by the Toulouse-based collector E. Barry (1809–1879), who was the first to report the find in 1869. The numismatist É. Taillebois (1841–1892) dedicated a study to the jewellery in 1881, a study later taken up by M. Feugère in 1985. It emerged that the items originated from a workshop in the Adour basin and dated from the mid-3rd century, their craftsmanship being of lesser quality.

The coins were dispersed among several individuals from the time of their discovery: Commandant Clouzaud and General Beauchamp each had some, as did several members of the Société de Borda in Dax, including É. Taillebois (2 examples). Four were recently rediscovered in the coin cabinet of the Musée de Borda (Campo 2019, pp. 110–111 and 120) among earlier donations. According to data collected around 1881–1882, the coins ranged in date from the reign of Nero to those of Aurelian and Tetricus father and son—that is, up to around 274. The museum’s selection includes three denarii of Septimius Severus, Elagabalus, and Severus Alexander, and thirteen antoniniani from Gordian III to Postumus (2 of Gordian III, 1 of Philip I, 2 of Trajan Decius, 1 of Etruscilla, 1 of Trebonianus Gallus, 1 of Volusianus, 1 of Valerian I, 2 of Gallienus, 1 of Salonina, and 1 of Postumus).

Due to the discovery in the Rhine riverbed at Hagenbach (Germany) of a group of silver items from Aquitaine, interpreted as booty, the Donzacq hoard may be linked to the Germanic incursions into the province in 275. As its contents include no coins of Probus (276–282), the year 275 appears to mark the burial of this deposit in connection with those events.

Photo : @ GrandPalaisRmn (National Archaeology Museum) / Franck Raux / Dominique Couto

-

The Éauze Treasure

The Éauze Treasure

Gold, silver, copper alloy, bone, hard stones 3rd century AD; Éauze (Gers) Deposit at the Musée d’Éauze Saint-Germain-en-Laye, National Archaeology Museum

The Éauze Treasure was unearthed in 1985 during a rescue excavation carried out at the site of the ancient city of Elusa by the Department of Historical Antiquities of the Midi-Pyrénées region.

The circumstances of the discovery allowed for a thorough excavation of the treasure, and numerous observations were made regarding the arrangement of the deposit. The treasure had been placed in a circular pit measuring 50 cm in diameter, with a preserved depth of 28 cm. It consisted primarily of a mass of 120 kg of billon coins and a substantial collection of gold jewellery. The 28,000 coins were most likely divided into four bags, one of which retained its shape and was identifiable during the excavation.

The coin hoard spans the period from the reign of Commodus (177–192), through Gallienus (253–268), to Postumus (260–268). The most recent coins enable the burial of the treasure to be dated to the year 261.

The jewellery includes necklaces, bracelets, earrings, rings, as well as a few cameos and intaglios. The collection is typical of the 3rd century AD. The style of the gemstones and the shapes of the necklaces and bracelets suggest they were produced in a workshop located in the Rhineland, between Cologne and Bonn.Photo: © GrandPalaisRmn (National Archaeology Museum) / Gérard Blot